En su trayectoria como crítico de cine y profesor universitario, a Alberto Fijo le han pedido muchas veces consejo, listas y títulos después de una clase o conferencia. Siempre responde que no le gusta aconsejar sin conocer a fondo al espectador. Eso no quiere decir que no lo haga, pero prefiere mostrar y expresar lo más valioso que ha encontrado en una película con la intención de poder compartir ese tesoro.

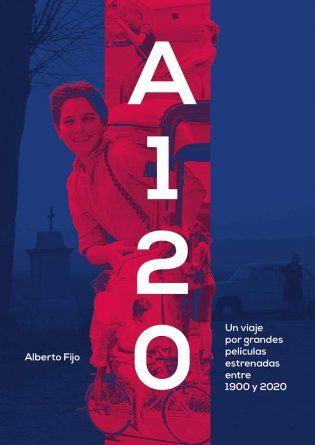

A 120. Un viaje por grandes películas estrenadas entre 1900 y 2020 es una historia del cine en miniatura. Una selección de las películas que el autor ha vuelto a contemplar una y otra vez. Ante la avalancha de nuevos títulos y opiniones telegráficas (y muchas veces pasionales), que se vierten a diario en medios de comunicación y redes sociales, este libro ofrece una pausa que se agradece. Un antídoto contra lo inmediato y efímero. Películas que han marcado la sensibilidad de autores y espectadores desde el año 1900 hasta 2020. Desde el Viaje a la Luna, de Georges Méliès, hasta Mank, de David Fincher.

El autor ha acertado al no incluir una película al año, sino que ha preferido liberarse de esta estructura tan recurrente y asfixiante. Así, incluye 13 películas de 1952 y 1953 (entre ellas, El hombre tranquilo, una de las obras maestras de John Ford que no pertenece al género de wéstern), mientras que no incluye ningún título entre Mi vecino Totoro (1988), de su admirado Hayao Miyazaki, y Cuento de verano (1996), de Éric Rohmer.

Los comentarios de cada película son breves y sugerentes, atendiendo al recuerdo del primer visionado, el momento histórico en el que se rodó y las aportaciones estéticas que convirtieron a la película en necesaria y referencial. Cada capítulo anima al lector a acercarse al cine perdurable, a ese que no se olvida con el paso del tiempo.

Probablemente a muchos les extrañará que en este recorrido no haya incluido títulos tan esenciales como Ciudadano Kane, Vértigo (De entre los muertos), Cantando bajo la lluvia, Centauros del desierto, El apartamento, Blade Runner, Sin perdón o La ciudad de las estrellas (La La Land). Títulos que admira, pero que ha preferido no seleccionar en favor de otros menos conocidos que sorprenden por su personalidad creativa: La kermesse heroica (1935) de Jacques Feyder, Lazos humanos (1945) de Elia Kazan, Me siento rejuvenecer (1952) de Howard Hawks, Tempestad sobre Washington (1962) de Otto Preminger, El árbol de los zuecos (1978) de Ermanno Olmi, o Aguas tranquilas (2014) de Naomi Kawase.